by ASSEMBLEA DONNE DEL COORDINAMENTO MIGRANTI

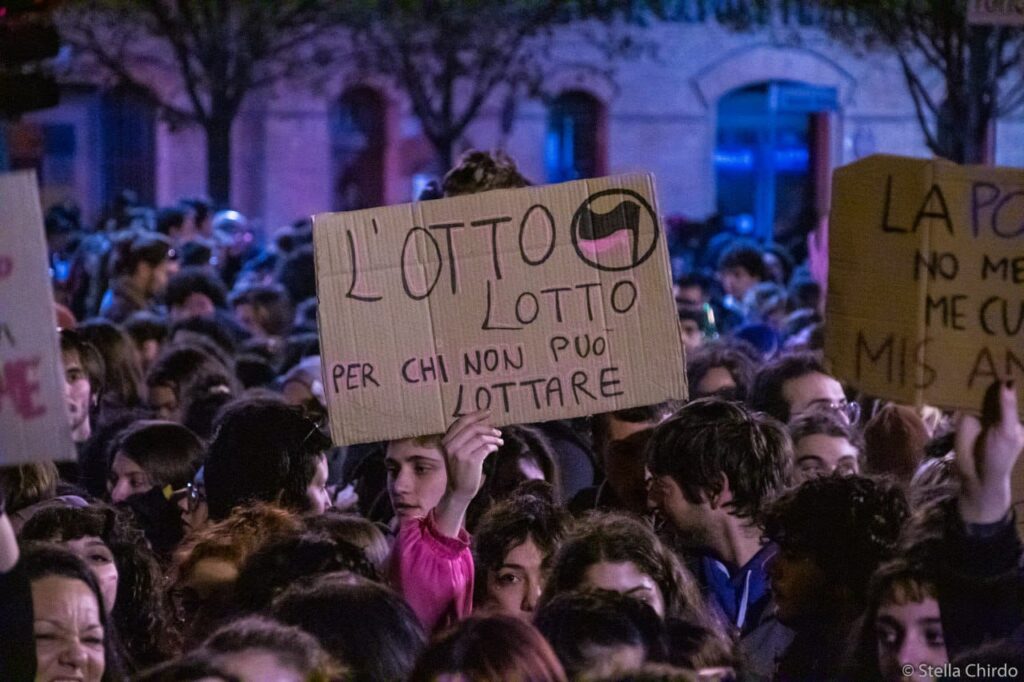

Two years after Russia invaded Ukraine, and after October 7th and months of genocidal violence against the Palestinian population by the State of Israel, the feminist and transfeminist movement is keeping the chance of fighting in this world of war open. On the 25th of November, five hundred thousand of us were in Rome to say no to male violence against women. Two months later, the movement rose again in Argentina in the general strike against Milei’s government. On the 27th of January, hundreds of thousands of women revolted in Kenya against yet another femicide, exposing the government’s complicity: The state is not the solution, it is part of the issue. To keep this space of struggle open and widen it, we must fight against the colonization of feminism by the war logic. Refusing the militarist ideology and its patriarchal cult of honor, discipline, force, and weapons; opposing the normalization of violence; organizing against increasing exploitation while rearmament expenses are growing; fighting against islamophobia, antisemitism, and nationalism that are arming racism; being a collective force against the war and its material effects on our lives, reclaiming the end of bombardments in Ukraine and the genocide in Gaza, saying no to the militarization of society and state violence: this is the challenge of the feminist and transfeminist strike of the 8th of March.

Striking for us means creating a dialogue between women and queer people living and working under different conditions and organizing to break the identities imposed by oppression. Women workers who have emptied citizenship and a poor salary; black and migrant women doing essential work to renew their residence permit; Russian and Ukrainian; Palestinian and Israeli, Turkish, Kurdish, and Iranian women and queer people who are taking a stance against the war and the blind Israeli violence in Palestine. This is the intersectional and transnational feminism we need. To practice it, we need to come to terms with the privileges that divide us. But it is not possible to do that if the history that produced them is only recalled to build unmodifiable identities, if privilege is evoked like a cudgel to censor those who disagree, to impose silence on the fights. We are an assembly of Italian and migrant women. We know that having black skin means enduring the racism that presents the history of colonization and slavery, but we also know that white privilege means little for a worker from the East who has to renew her work permit or for an Italian factory worker who had to quit her job after the pandemic and doesn’t even have minimum welfare benefits anymore. The women’s fight in Kenya shows that even those who have suffered colonial violence can become agents of male violence. Racism, male supremacy, and class dominance cross borders. The fight against them must too. It is not enough to recognize given privileges, fixing those who can incarnate them and those who don’t in the unmodifiable positions of oppressor and victim with their hierarchies. As bell hooks wrote, privilege is a practice, not an identity. You can be born white and fight every day against racism and exploitation. Or you can embody that privilege, treating migrant, black, and working women like victims of pity instead of taking strength from their everyday struggles. Decolonizing our minds is not enough to practice transnational and intersectional feminism. We must organize to fight against the social conditions that create privilege.

Fighting against privilege means fighting against the normalized racism of war logic. The Cutro decree, the project to build detention centers in Albania, the fiscal persecution of migrant domestic workers programmed by Meloni’s government, the convergence of the UK, the EU, and its states on the externalization and militarization of borders, Islamophobia, and the repression of those who, in Germany and the United States, can’t fight against racism without being accused of antisemitism—everything converges to limit the freedom of movement as much as possible. Everywhere, right-wing forces wave a maternity ideology that hides the silent exploitation of migrant women, more and more necessary for essential services crushed by cuts to public expenditure in the name of the rush towards rearmament. Racism is an issue for our movement because it digs deep trenches that divide and limit our capability of building an intersectional fight.

We must overcome those trenches if we want to be part of a transnational mobilization against the war that doesn’t just reclaim a ceasefire because it does not accept a peace made of sexist oppression, racism, and exploitation. We don’t believe in territorialized politics, where only those who live under oppression are authorized to speak, freeing us of the responsibility of taking a stance because we have the privilege of not being under the bombs. We don’t even think, like some men who want to lecture feminists on how to fight, that we can represent the conditions of those who live under the bombs as homogenous, nor do we think we can establish for them what the best, or the only, way to resist is. Some flee, some do their best to try to reproduce life in a bombarded society, some hope that becoming part of neoliberal Europe will save what remains under the rubble of the war, and some find the only possible defense to Israel’s genocidal violence in confessional organizations for which patriarchy is a practice of governance of the territory and a political project because those are viable alternatives. But if the war puts those who directly suffer it face to face with these impossible alternatives, feminist politics must keep alive the possibility of a liberation that doesn’t reproduce male dominance and exploitation. Even the West, for which all historical responsibilities must be recognized, is not a monolithic front because millions are mobilizing to end the genocide in Gaza and because multiple fights are tormenting it. That’s why we find a feminist strength in the protests organized together in the West Bank by Israeli and Palestinian women. Kurdish and Iranian women who sided with the Palestinian fight without supporting the Axis of Resistance showed us the possibility of breaking the fronts imposed by war. For this reason alone, they are today ignored by portions of the movements that, until yesterday, considered them a driving force for global feminism. And yet, their message is clear: there will be no liberation until patriarchal oppression continues. This is the challenge we face, which calls for dealing with the contradictions created by the war without fear like Non Una di Meno started doing during its national assembly.

We wonder what will be there after the bombs, and we know that the war is trying to write that answer. To have our say, we must know that we cannot be free if, in Ukraine or Israel, the highest form of emancipation promised to women and queer people is the army. We cannot be free if women in Russia are arrested for exposing the poverty that forced their sons and husbands to go to war while rich men could flee. We cannot be free if, in the name of “decolonial feminism,” we treat Israeli and Russian women opposing genocide and the war as enemies and instead stand in solidarity with the oppressive regime in Iran that targets women and queer people, or the Turkish government that is repressing with weapons the Kurdish revolutionary project and those who fight for it. We cannot be free if, after the ceasefire, a reconstruction made of capitals that profit off prolific mothers, sexual discipline, and male authorities to keep everything in order starts.

We expect that on March 8, in Italy, these transnational intersections will be expressed by many voices. The voices of the working women who can unite their fragmented fights against exploitation and make them visible in the common refusal of male violence; those of young women, queer people, and men who after Giulia Cecchettin’s femicide discovered the possibility of liberating their present from the violent authoritarianism of patriarchy; those of migrant and black women who don’t accept to work, live and love under the blackmail of racism; the voices of those who in the past months mobilized against the war and for the end of the genocide in Palestine, taking to the streets not only to claim the ceasefire, but also to take back the fight against racism, oppression, and exploitation fueled by war; of those who don’t believe that this fight is weakened or divided by feminism, but on the contrary believe that feminism is necessary to strengthen that fight. The feminist and transfeminist strike is our opportunity to create a dialogue between different conditions, to activate processes and relations enabling us to be the crisis of the order that’s oppressing us, to take a stance against the war that wants to pacify our fights, to support the end of the siege in Rafah and the ceasefire in Gaza with the strength of our rebellion against the patriarchy, and to attack with that same strength that society that produces privileges. This transnational and intersectional feminism is the only privilege we want to practice, to make the 8th of March strike the opportunity to overrun the identities produced by dominance and break their isolation.

Coordinamento Migranti Il Coordinamento migranti Bologna e provincia è nato nel 2004.

Coordinamento Migranti Il Coordinamento migranti Bologna e provincia è nato nel 2004.