With the crises and transformations of Europe’s wartime economies, states and the EU are relentlessly pursuing the goal of forcibly governing the movement of migrants within and beyond Europe’s borders. Today’s policies are nothing new, but as the ideology of borders to be defended at all costs is increasingly propagated, we see how the Third World War is an opportunity to promote and legitimise racist and increasingly punitive policies against migrant women and men. Germany and England are drawing up pacts for the deportation of migrants; France has passed a law to simplify the mechanisms for the expulsion of migrants and to speed up refusals; in Greece, violent rejections continue. The new EU Pact on Migration and Asylum enshrines these policies at the transnational level, effectively emptying the right to asylum and establishing accelerated procedures for repatriation or deportation to those third countries that are deemed safe. The fact that migration policies are now embedded in the politics of war is further highlighted by the double standards of the European Union, which, while militarising its borders, has allowed millions of Ukrainian refugees to enter, thus demonstrating the political and arbitrary nature of border violence and entry management. However, this has not protected Ukrainian arrivals in European countries from having to deal with everyday institutional racism.

This is the background to the manoeuvres of the Italian government, whose involvement in the war scenario is substantiated by a violent attack on migrant women and men. Since taking office, Meloni has used proclamations and racist laws to cultivate the illusion of being able to stop the movement of women and migrants towards Europe. The year 2023 began with an attack on the activities of NGOs in the Mediterranean, forcing them to disembark at the port indicated by the Coast Guard. We saw ships full of migrants sail for days across the Mediterranean; we saw an increase in the number of victims among those who continued to defy the borders, with around 1,000 more deaths than the previous year. The year 2024 began with an attempt to take this racist offensive beyond national borders, using the weapons of bilateral agreements and cooperation plans. With the approval of von der Leyen and the European institutions, the Italian government launched a campaign in Albania to overcome the difficulties of building new detention centres in Italy. An agreement between the two countries provides for the construction of two reception centres on Albanian territory, which will be able to accommodate up to 3,000 migrants. A couple of weeks ago, the Albanian Constitutional Court approved the agreement, and the government announced that the centres, which will be paid for and managed by Italian staff and under Italian jurisdiction, will be built by this spring. Migrants destined for these centres will no longer pass through Italy: once intercepted at sea, they will be deported directly to Albania, where they will be detained in facilities inaccessible to NGOs for as long as is necessary for their repatriation.

The much-hyped ‘Mattei Plan’ also continues the politics of externalising borders that the European Union has been pursuing for some time, including in energy and climate policy. Launched to revitalise Italy’s role in the Mediterranean, the plan takes up the battle cry of ‘helping them at home’ to promote an equal partnership with African states based on strategic pillars such as energy, education, agriculture, water, and health to guarantee the ‘right not to emigrate’. Meanwhile, in line with this legal invention, Foreign Minister Tajani has announced the suspension of funding for UNRWA, the UN agency for Palestinian refugees, following allegations of the involvement of some officials in the Hamas attacks of October 7, without caring that it is only the hundreds of thousands of displaced men, women, and children in Gaza who will pay the price.

But Giorgia’s war against migrants is also made up of small things, far from the limelight. The latest news came with the budget law, which increased the cost of registering with the National Health Service for migrant students and migrants over 65 who arrived through family reunification. The cost rose from 149 to a whopping 700 euros, an exorbitant increase that sends a clear message: if you don’t work, we don’t need you, so you pay! The same law also excluded domestic workers, 80% of whom are migrants, from the benefits provided for mothers with two or more children. The tradition of squeezing migrants by making them pay to stay continues.

These measures deepen the authoritarian stranglehold on migrants that began with the Cutro decree, which effectively abolished special protection, limited the ban on deportations, funded the construction and expansion of repatriation centres (CPRs), and cut basic reception services such as legal aid and psychological support. In recent months, migrants’ complaints have shown what this has meant for their lives. After the decree, the delays of prefectures and police headquarters in issuing documents were joined by the new front of mass rejections of asylum seekers. The accelerated procedures are summary processes that are only useful for issuing refusals; with the negatives, migrants are given deportation orders that force them to choose between leaving the country and becoming illegal immigrants. The drastic cuts in funding for ordinary reception facilities have led to the proliferation of supposedly emergency centres where migrants are packed together en masse, often in the remotest suburbs, only to be sent to work for starvation wages in logistics warehouses or the countryside. Migrants denounce and struggle daily against the conditions in these centres and the deterioration of the already unbearable situation.

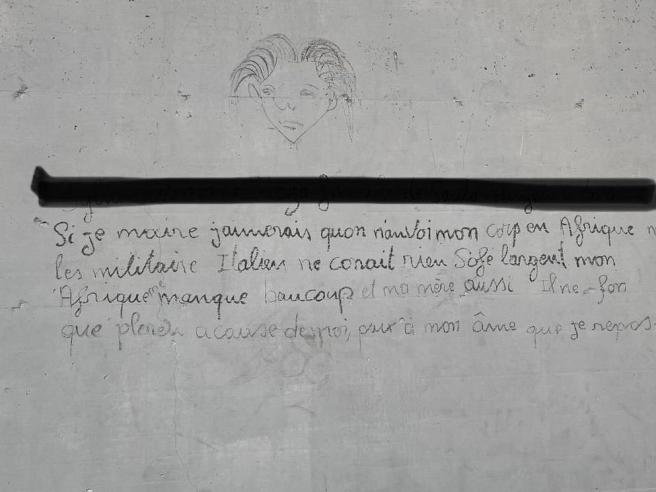

For months in Bologna, Piacenza, Rimini, and other cities in Emilia-Romagna, migrants organised in the Assembly of Migrants of the Mattei Centre have been denouncing the conditions in which they are forced to live, the delays in receiving pocket money, and the institutional racism of prefectures and police headquarters that delay procedures for residence permits. In recent days, in the CPR of Trapani, around 140 migrants who were sleeping outside on the ground without mattresses set fire to the building, rendering it almost completely uninhabitable. In the CPR of Ponte Galeria, in Rome, a young migrant called Ousmane Sylla committed suicide to put an end to his endless detention, which led to protests and riots by the migrants of the centre, which were suppressed with the use of tear gas. Last of all, the migrants of the CPR of Milan lay down in the rain to protest against the uninhabitable situation inside the centre, which had already been commissioned by the Public Prosecutor’s Office for its ‘inhuman conditions’. A few hours after the start of the protest, the police, called in by the centre’s staff, forcefully entered the centre, beat the migrants with truncheons, and broke the leg of an 18-year-old boy. The CPRs and the centres that the right-wing government is outsourcing to Albania are just the tip of the iceberg of a politics of violence and death that extends far beyond the Mediterranean and the border regions.

Migrant women and men continue to challenge these policies with their mass arrivals, fighting against the fate of violence and poverty that governments would like to impose on their lives. We must ask ourselves whether we should leave them alone in their struggle against this new normal of violence and death. In Germany, more than a hundred thousand people took to the streets against the AFD’s plan to deport migrants. This is certainly important. But we need to recognise that what might look like a mere racist dream of the far right is already being realised in Italy and across Europe. As the new EU Pact on Migration and Asylum shows, there is a continuity between ‘democratic’ European policies and state policies that have destroyed the right to asylum, promoted the militarisation of borders, and strengthened institutional racism. In the shadow of a Third World War, which legitimises ever harsher laws against those who, despite Europe, continue to violate Europe’s borders, we see a new condition of exploitation and oppression emerging, which affects everyone. The subordination and deportation of women and migrants will in no way compensate for the continued impoverishment of those who work with citizenship in their pockets. The war against migrant women and men is part of the war in which we are forced to live and work and against which we must fight. Today, more than ever, being on the side of and with migrants also means taking a stand against war, and rejecting war means being on the side of and with migrants. The solidarity that so many have expressed in recent years and continue to express must be transformed into a visible struggle; their movement contains a call for peace that resonates powerfully and must be heard and supported in order not to give in to the lure of the sirens of war.

Coordinamento Migranti Il Coordinamento migranti Bologna e provincia è nato nel 2004.

Coordinamento Migranti Il Coordinamento migranti Bologna e provincia è nato nel 2004.